PAs: It’s Time to Talk About Suicide

Be Alert and Take Initiative with Patients

March 21, 2019

By Hillel Kuttler

During a checkup 14 years ago, a medical provider noticed that Larry Flick seemed a bit down. After checking Flick’s blood sugar, he asked whether taking diabetes medication made him sad.

That intuition was accurate, because Flick, a radio broadcaster in New York City, recalls having had “multiple days of borderline suicidal depression” then. Flick was prescribed an anti-depressant. In subsequent visits, he reported improvement.

“Without a doubt, he saved my life because he zeroed in,” Flick said. “I think it’s of dire importance that [providers] ask questions.”

Being alert and taking the initiative are central to a suicide prevention effort following passage of an AAPA House of Delegates’ resolution last May on the matter.

The resolution directed AAPA to develop information for members, and to include the information both in CME activities such as an AAPA 2019 session “It’s Time to Talk About Suicide,” and in PA programs’ curricula through the Physician Assistant Education Association.

Report recommends standard care for suicide risk

It also endorsed the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention’s 2018 report, “Recommended Standard Care for People with Suicide Risk: Making Health Care Suicide Safe,” as a guide for PAs.

The report cited studies finding that approximately half of those who died by suicide were seen in a primary care setting within the previous 30 days; in large healthcare systems, more than 80 percent were seen in the previous year. Almost 40 percent of suicide victims had visited an emergency department without a mental health diagnosis, the report stated.

“Healthcare organizations have a unique opportunity to help prevent suicide,” the report said. As for primary care providers, it acknowledged that while universal screening for suicide hasn’t yet been recommended, “it is essential to explicitly consider suicide risk among all patients who present key risk factors,” such as those with a diagnosed mental illness, substance use disorder, or who are taking psychiatric medication.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 47,173 people died by suicide in the United States in 2017. Suicide was the second leading cause of death that year for ages 10–34 and fourth for ages 35–54. From 2008 to 2017 suicide rates increased 22%.

All PAs are psychiatric PAs

“All PAs are psychiatric PAs, whether you specialize in it or not,” said Phyllis Peterson, MPAS, PA-C, DFAAPA, a PA on the psychiatry department’s faculty at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center and president of the Association of PAs in Psychiatry (APAP). “Most PAs in any practice see people with mental health disorders or issues. They often don’t get discussed or treated thoroughly at all.”

The PA Foundation is working to provide tools to help. In March 2018, it awarded Mental Health Outreach Fellowships to 16 PAs to become certified to teach the National Council on Behavioral Health’s Mental Health First Aid (MHFA) curriculum. The eight-hour course equips participants to detect patients with mental health crises and to intervene. Through the Foundation’s program, PA Fellows committed to training a minimum of 100 people in their communities.

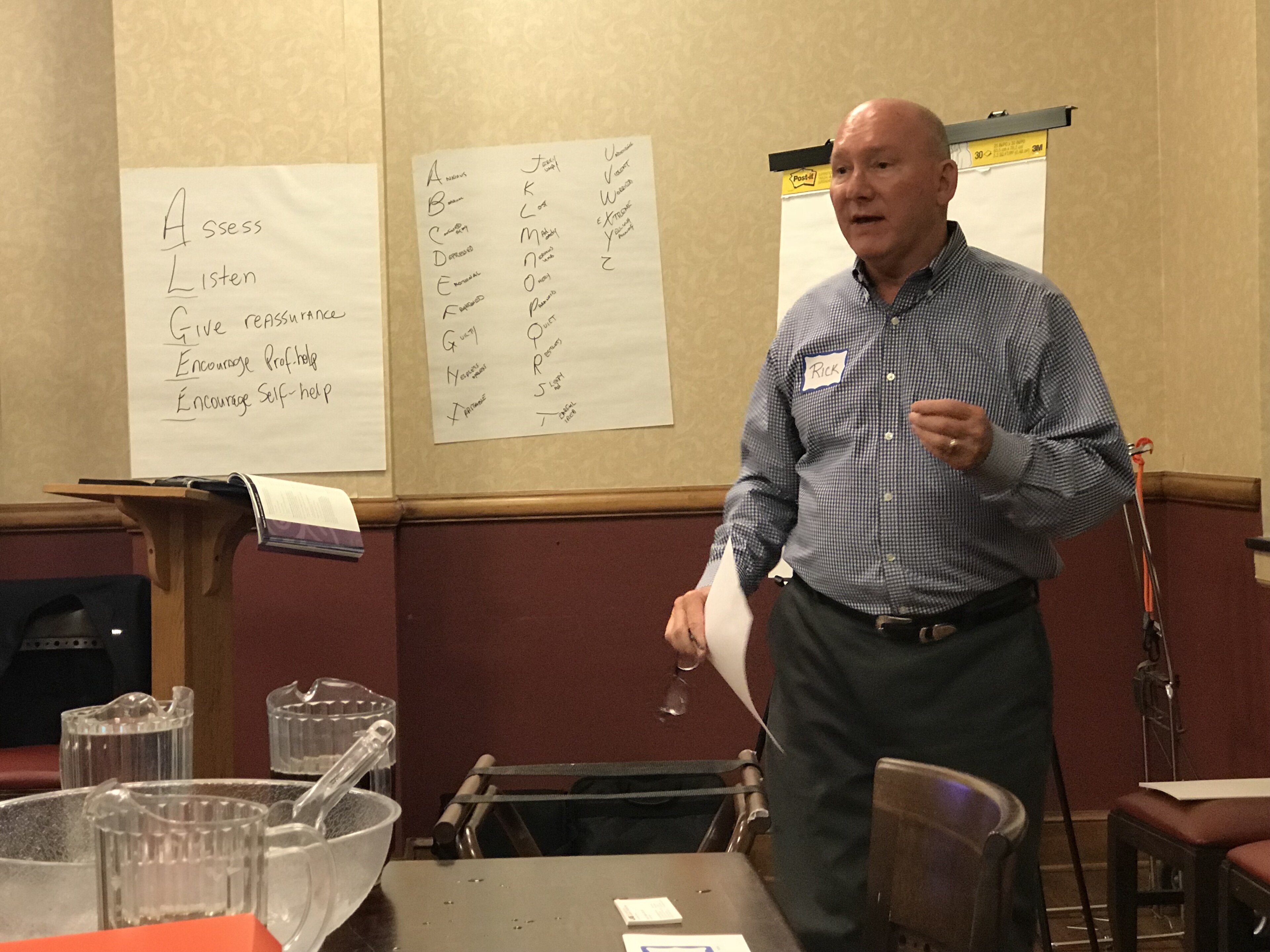

One participant, Laura Allen, MS, PA-C, went on to lead classes for corrections officers at the Denver facility where she performs medical screenings for arriving inmates. Another PA, Rick Kilgore, PhD, PA-C, DFAAPA, ran classes for staff at homeless shelters and rural health clinics near Birmingham, Alabama. Melodie Kolmetz, PA-C, taught both public-safety officers at the Rochester Institute of Technology in New York, where she is an assistant professor in the PA program, and local firefighters and emergency medical technicians.

Firefighters and EMTs with whom Kolmetz has worked in ambulance services for nearly 30 years have mentioned feeling ill-equipped to treat people experiencing mental health crises, “so I knew there was a need for better education,” she said.

Addressing suicide directly a relief

Learning to ask patients directly if they are depressed or are contemplating suicide was an eye-opener for Allen.

“Saying the word suicide if someone is depressed is often a relief [to the patient] – that ‘Oh, I can talk about it with this person,’” she said.

Said Robert Sobule, PA-C, a PA in University of Missouri Health Care’s psychiatry department: “When you’re doing any evaluation, you’re not going to gloss over [someone’s reporting] chest pains or shortness of breath, so why would you skip over asking how your mood’s been lately and how you’ve been doing lately?”

Allen drew on the course’s lessons when she noticed that a colleague in the prison clinic, a nurse, had experienced several consecutive bad days. Allen spoke with her, then asked a supervisor to follow up. These days, Allen said, the nurse seems fine.

“Little things like that can head off a worse scenario later,” Allen said. “MHFA training encourages you to reach out.”

Offering the fellowships came about after a survey of PAs revealed mental health intervention “at the top of the list” of programming the Foundation should pursue, said its executive director, Lynette Sappe-Watkins.

“Our mission is to empower PAs to improve health through philanthropy and service,” she said. “It’s our responsibility to equip PAs to go out into the community and lead healthcare initiatives.”

Free resources to discern symptoms

Jay Somers, PA-C, owner of a family psychiatry practice in Las Vegas, recommended that primary care providers use such free resources as the seven-question Generalized Anxiety Disorder questionnaire (GAD-7) and the nine-question Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), to screen patients’ mental health. They can follow up with the Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ) to screen for bipolar symptoms, he said.

The answers “give us a window into what’s happening” and how often the symptoms impair someone’s ability to function, he said.

Sobule recommended that screenings be supplemented with the knowledge of available resources to address a patient’s needs, such as referrals for counseling and availability of emergency treatment.

“A lot of times, providers can be scared to do the screening: ‘If I find something, what do I do?’” Sobule said.

Peterson recalled that when working as a medical practice’s receptionist early in her career, a patient mentioned feeling suicidal. The nurse who was seeing her panicked, but a physician spoke with the patient and arranged for hospitalization. It turned out that the woman’s spouse was abusive, leading her to become depressed. In follow-up visits, she had improved.

“The more we talk about it, the less strange it is, the more it will be seen as something we need to help with, just like if the patient says their foot hurts, or anything else. If someone says they’re having a heart attack, you don’t panic. There are steps you take,” Peterson said.

For some, suicide hits close to home.

Several years ago, an APAP board member died by suicide. Catherine Judd, PA-C, knew the man. At AAPA 2019, in Denver, she’ll be leading a session called “It’s Time to Talk About Suicide.”

Said Judd, a board member of both APAP and the PA Foundation: “Every PA – I don’t care if they’re in oncology, radiology, trauma, or surgery – needs to be comfortable asking and screening patients for suicide risk factors.”

If you or someone you know might be at risk of suicide, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255, or visit suicidepreventionlifeline.org.

More Resources

PA Program Prioritizes Student Mental Health

PA Aims to Stop Opioid Addiction Before It Starts

Hillel Kuttler is a freelance writer and editor. He can be reached at [email protected].

Thank you for reading AAPA’s News Central

You have 2 articles left this month. Create a free account to read more stories, or become a member for more access to exclusive benefits! Already have an account? Log in.